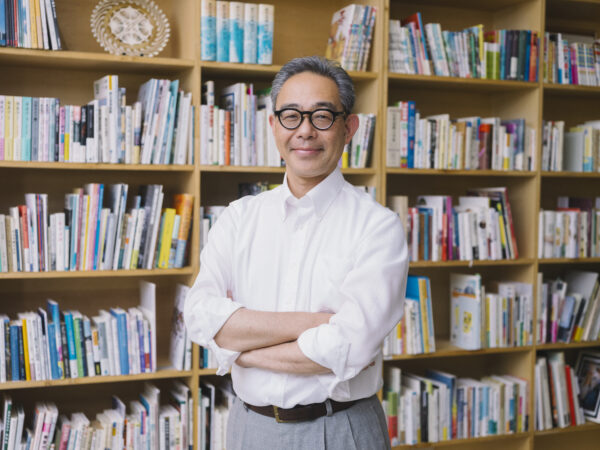

Integrating Art into Life in Changing Times: An interview with Director of Tokyo Artpoint Project Mori Tsukasa

執筆者 : Sugihara Tamaki(Interview and text) , William Andrews(Translation)

2025.05.21

2025.05.21

執筆者 : Sugihara Tamaki (Interview and text) , William Andrews (Translation)

*This is a translation of an interview originally published in the Tokyo Artpoint Project annual report Artpoint Reports 2023→2024 (March 25, 2024).

―

What kind of year was 2023 for people working in the cultural sector? Mori Tsukasa describes the role of culture in troubled times.

Though it felt very much like things had finally restarted after COVID, such as in how we were able to hold the Artpoint Meeting three times, 2023 was nonetheless a year in which we began to encounter the situation the pandemic had ushered in. We can now hold events like normal, but both organizers and participants felt that something didn’t feel right about cultural projects undertaken in the same way as before, using the same operating system, so to speak. In which case, what is the new OS we should use? It’s still not apparent. The year was filled with a sense of that disparity.

This feeling of being out of joint with the times is even stronger for people working on “seasonal” projects, such as large-scale events that match current social trends. Three projects co-organized by Tokyo Artpoint Project since 2022—Karoku Recycle, KINO Meeting, and Metote Lab—are engaging with these universal challenges and social problems. They are certainly not flashy initiatives, nor do they even seem like art projects at first glance, but they are incredibly inclusive and represent one of the goals of Tokyo Artpoint Project, which advocates interaction with everyday life.

In the way that they involve a wide range of participants, not just so-called arty types, but people directly connected to the respective issues. Also, in the way in which the projects are not about someone doing something unilaterally, but through learning from one other. And they don’t just learn from other people but also nature, history, and so on. These projects are notably different from the ones Tokyo Artpoint Project ran in its early years that centered on famous artists.

And that these three projects are able to work like this is because they are led by people who are designers, interpreters, or artists who listen to people, or originally had a background as a kind of mediator. The nonprofits involved are developing and playing intermediary support roles between society and certain issues, which formerly program officers like us would have done.

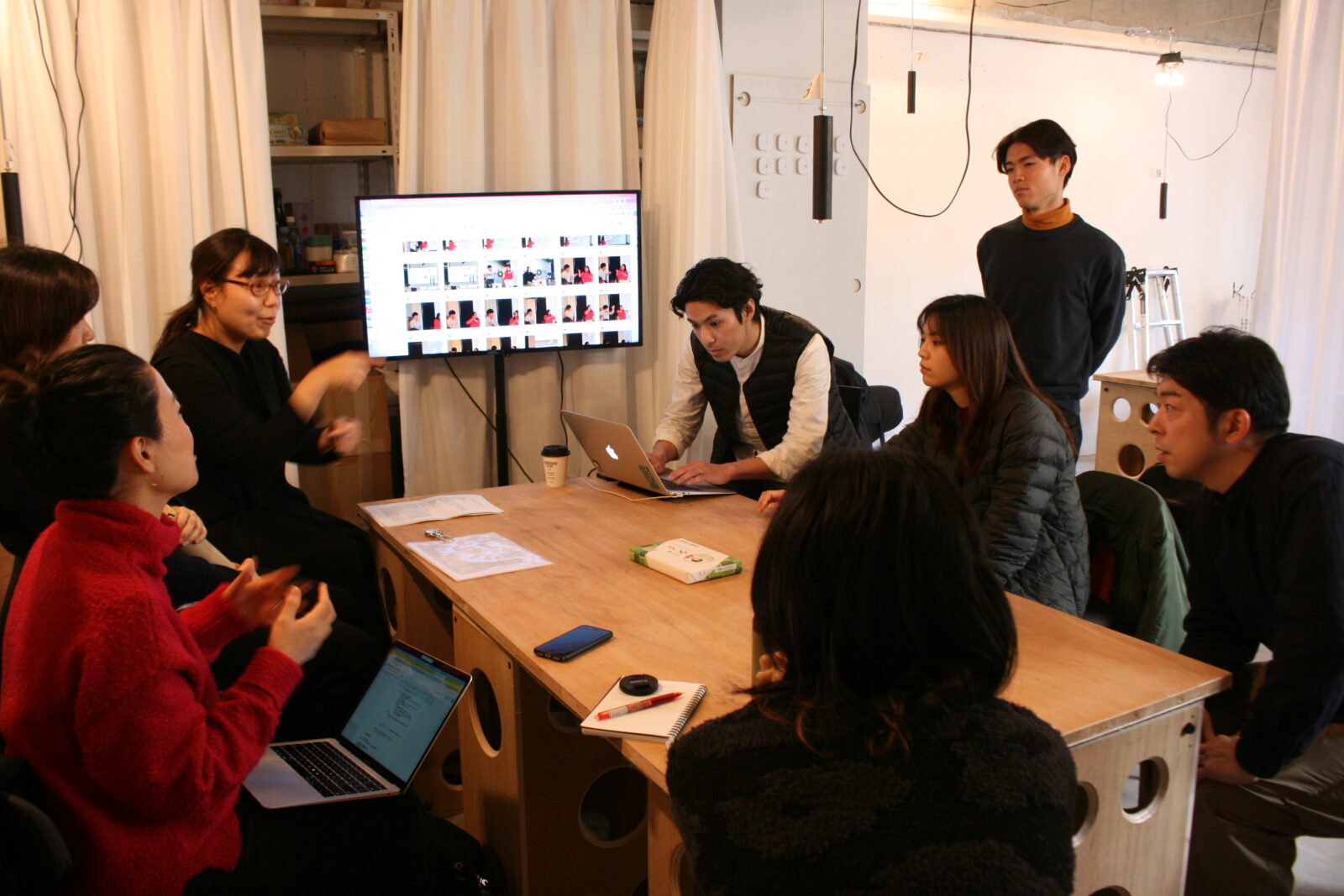

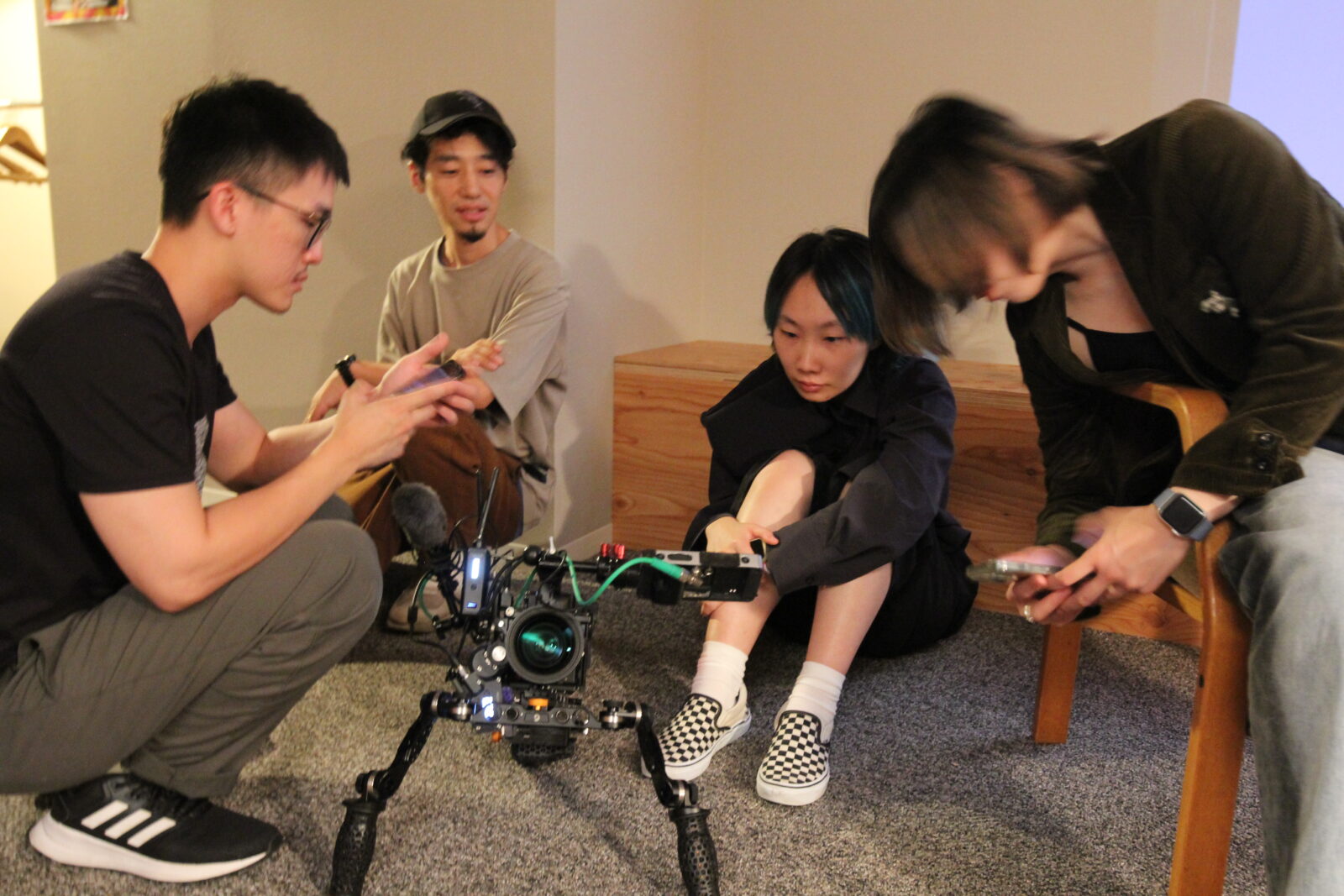

KINO Meeting, for instance, runs filmmaking opportunities for foreign-born residents in Japan, and the key point here is that the project treats filmmaking as the purpose for everyone coming together, and individual attributes as their qualifications for participating. This approach enables more people to take part easily and leads to opportunities for meeting and interacting informally with other people who have been in Japan for different lengths of time and whose Japanese language ability may not be the same level.

In Metote Lab, various kinds of families come together, including deaf parents with hearing children, or vice versa, or families where all members are deaf, and the project thinks about how signing is used in everyday life or ways to cultivate Deaf culture. The project is fully open to anyone with an interest in these questions. I think it’s important because the participants are not passive but “players” with their own backgrounds and connections to the issues, and the project functions as a collective of these individuals.

We have this unfortunate tendency to lump everyone together into generalized categories—deaf people, disaster victims, foreign-born residents—but these three initiatives build intermediary support structures while engaging carefully with people on an individual basis. This is a feature that distinguishes the projects from conventional efforts by other Tokyo Artpoint Project partners.

One was the screening and talk that KINO Meeting held at an independent movie theater in the autumn. It was a small-scale event in which there were almost as many attendees as speakers.Nonetheless, the event gave off a sense of grasping something as a project, including in terms of how the venue was managed and the relationships between participants, and it felt like a comfortable gathering for the members of the project too. The other two projects likewise usher in relaxing and mentally safe environments, and places where individuality is tolerated.

Recently, I’ve wondered if we should aim to run projects as “1.5” places. In sociology, the home is regarded as the first place, while the workplace or school is the second. Third places are other kinds of community spaces like a neighborhood coffee shop or church. But today, none of these places are stable or adequate. Our domestic circumstances are difficult, and many of us don’t have time to frequent the traditional kinds of third places. Instead of making these broad divisions of first, second, and third, perhaps what we need is a mindset of trying to join them together and find intermediary places.

For example, Karoku Recycle is based in a public housing complex and functions as a kind of 1.5 place for the residents, somewhere that’s near their homes (the first place) but still outside the home. Fantasia! Fantasia! likewise partners with the welfare sector, while Artist Collective Fuchu engages in creative activities using leftover materials provided by local businesses. In the sense that these projects open doors a bit and connect two different spheres, they are operating as 1.5 places. The kind of liminality that comes into view when we use this “1.5 place” label is, I think, the sphere where culture can function the most today.

People find life harder and harder and other spheres have reached an impasse. Against this backdrop, culture is able to change our perspectives and how we view things. For instance, what people in the welfare sector might call going for a walk or just going out becomes, for people working in culture, “research,” and this changes mindsets. Wandering around the community in a group might look suspicious, but KINO Meeting treats this process as filmmaking and it transforms the way that participants see the world. Changing perspectives is a truly fundamental function of culture and might seem like something quite basic. But our job today is about doing this kind of small-scale task.

Yes. In the first place, what we call art is actually synonymous with questioning norms. These three initiatives enable practices that question the existing “operating systems” of art. Because this is so novel, it can be difficult to describe or understand, but that’s precisely why Tokyo Artpoint Project should research and develop this kind of area that’s needed for the future.

In that sense, the projects we are doing now do not have conventional outputs like artworks and so on. It’s like what I just said about shifting to a smaller perspective. What lies behind these shifts in our projects is perhaps an increased sensitivity towards ableist values through our involvement with accessibility over the past few years. Ableism is a form of discrimination and social prejudice that prioritizes non-disabled people, defines people in terms of whether they can or cannot do something, and favors the ability to do things. Society today is overwhelmingly ableist.

But not being able to do something and what a body that has an illness or disability does is also a form of physical expression. Like with 1.5 places, a rich and meaningful world might well exist between ability and disability. We have to look more carefully at that. Because we’re living in an age in which conventional values are rapidly collapsing.

At such a time, we need creative culture that questions values, rather than culture that is consumable like content. That creation is not something far removed from the everyday but rather the small, fundamental workings of culture, like the shifts in perspective and viewpoints I previously mentioned. In these troubled times, many people need to feel directly connected to that power of culture.

Not trendy topics, but small, universal, and constant. That’s the kind of conscientious work people in the cultural sector need to do today.

―

Mori Tsukasa|Director, Tokyo Artpoint Project (Arts Council Tokyo)

Project Coordination Division Chief, Arts Council Tokyo (Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture)

Special Guest Professor, Joshibi University of Art and Design

Adjunct instructor, Tama Art University

Born in 1960 in Aichi, Mori Tsukasa worked from 1989 to 2008 at Mito Arts Foundation, where he was involved as a curator in the opening of Art Tower Mito’s Contemporary Art Center. He was responsible for curating various solo and group exhibitions, including Christo (1991), Tadashi Kawamata DAILY NEWS (2001), Katsuhiko Hibino: Hibino Expo 2005 (2005), and Tatsuo Miyajima | Art in You (2008).

In 2009, he joined the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture, where is involved with running art projects in communities in partnership with nonprofits as the director of the intermediary support program Tokyo Artpoint Project, and also oversees the Tokyo Metropolitan Government & Tokyo Municipality Collaboration Project.

From 2011 to 2020, he was director of Art Support Tohoku-Tokyo, providing help to areas of northeast Japan affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake through arts and culture. From 2015 to 2021, Mori was project director for the official Tokyo 2020 Cultural Olympiad programs Tokyo Caravan and TURN. He is currently involved with promoting Creative Well-being Tokyo and improving the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture’s accessibility.

執筆者 : Sugihara Tamaki(Interview and text) , William Andrews(Translation)

2025.05.21

執筆者 : Sugihara Tamaki (Interview and text) , William Andrews (Translation)

2025.05.21

執筆者 : Sugihara Tamaki (Interview and text) , William Andrews (Translation)

2024.11.27